Radhanath Sikdar Scaling Great Heights

Anindita Mazumder

Sikdarpara in Jorasanko was inhabited by Sikdars who wielded iron rods during the Nawab’s rule. Though Brahmins, they served as police commissioners, a hereditary post under the Nawab and wielded enormous authority, with a number of lathials, soldiers and sentries working under them. As often is the case, the protector turned into oppressor as well. Their influence continued into the British rule as representatives of the Nawab till a victim brought it to the notice of the Colonial masters who promptly abolished the practice.

By the time Radhanath Sikdar was born in 1813, his father, Teeturam or any other kin no longer followed their hereditary vocation. Those who believe that brain and brawn cannot go together would have been forced to re-evaluate their opinions since he had inherited enormous strength and physical attributes of his forefathers, their fearlessness apart from having a brilliant mind. His induction as a “computer” in Survey of India is perhaps a testimony of his brilliance. In college he went in for boxing bouts with goras, often to the latter’s disadvantages.

Keen to ensure his two sons, Radhanath and Sreenath acquire enough knowledge of English to land clerical jobs; Teeturam enrolled both in ‘Firinghee’ Kamal Bose’s school before they won scholarships for Hindu College. He was attracted by the teachings of the free thinker Henry Louis Vivian Derozio and joined his Academic Association. But unlike other Derozians who later moved towards spiritual quest he remained a man of science throughout his life. Radhanath was also tremendously influenced by Dr John Tytler who inculcated in him a deep love for mathematics and inspired him to read Newton’s Principia and works of Euclid and other books on trigonometry at a time when there was no institution for advanced science and higher mathematics.

Following his brush with free thinkers he refused to marry a child bride, choosing to remain a bachelor. Another consequence was his tremendous fondness for beef. He firmly believed beef eaters were never bullied. Meanwhile, economic, political and military interests of the British dictated the need for mapping the occupied territory to exercise full administrative control. The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, a part of a larger exercise of surveying the entire Indian subcontinent with scientific precision began under infantryman William Lambton, later succeeded by George Everest. It began from St. Thomas Mount, a small hillock in Madras and extended till Mussorie. The massive exercise which lasted four decades (1802-1841), claimed more Indian lives than the two world wars combined, including that of Lambton. Lives were lost to malaria, typhoid, cholera, sunstroke, frostbite, forest, rivers, avalanches and bandits. At this juncture, Everest was looking for natives, proficient in trigonometry and the young nineteen-year-old left college to support his family and found a job at Surveyor-General’s office in Calcutta for a monthly salary of Rs 30, following Dr Tytler’s recommendation. He was sent to Dehradun as a “computer” the first Indian to be inducted at that post and soon Everest acknowledged him as a “mathematician of rare genius,” a rare acknowledgement considering natives were not even allowed to touch the equipment.

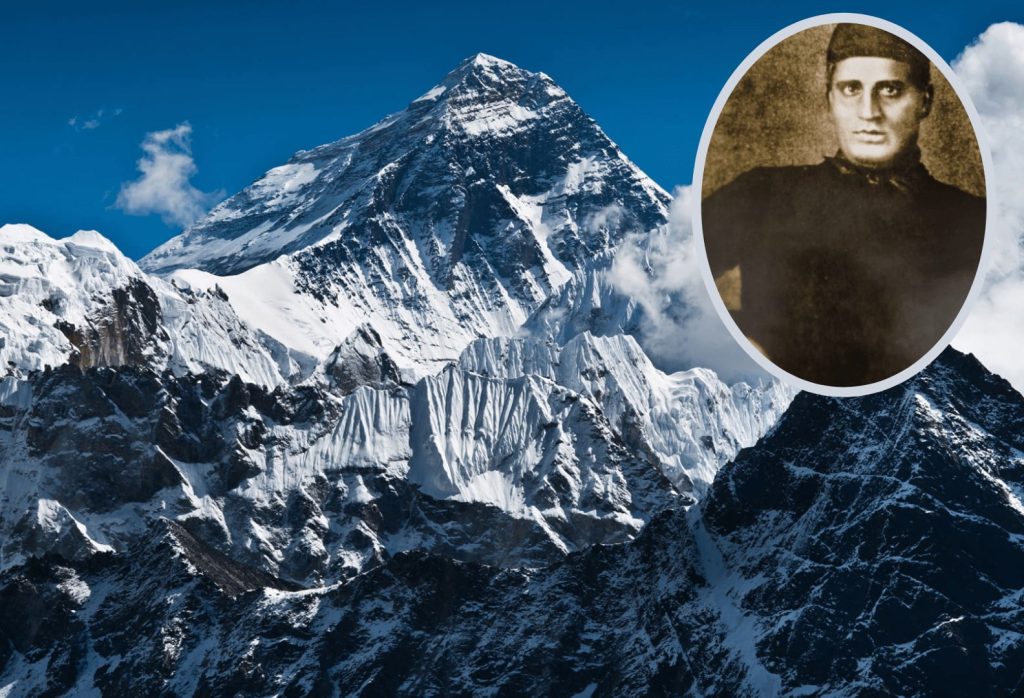

By 1851, Radhanath returned to Calcutta as Chief Computer. He had to derive actual geographical positions on ground from the raw geodetic survey data collected during field work by using complex equations. Everest’s successor, Andrew Waugh asked Radhanath to devise formulae for computing geographical positions and altitudes of snow peaks observed from distances of 100 miles. The unclear border divide between India and Nepal around Peak XV meant that Radhanath was asked to estimate its height using theodolite from 150 miles away. He calculated the height to be 29,000 feet. However, to avoid any implication that it was a rounded estimate, it was publicised as 29,002 feet! It was a terrific feat considering he worked out the allowance to be made for atmospheric refraction (the deviation of light from straight lines by the density of Earth’s atmosphere) which could have played havoc with his calculations. Although Waugh chose to wait for some time (till 1856) for repeated verifications, Radhanath Sikdar’s calculations identified Peak XV as the highest in the world. Till then many believed in Europe that the Alps was the highest.

Though lavish in his praise for Radhanath, Waugh, guided by imperialist tradition of ignoring scientific contributions of subjects, recommended the name of his illustrious predecessor, ignoring even the custom set by George Everest to name every geographical object after its local appellation. He cited their inability to ascertain the local name because of inaccessibility though another report suggested its Nepalese name was Deodhunga. Although Asiatic Society wanted to continue the search, Waugh convinced the Royal Geographical Society to accept ‘Mount Everest’ at least in England.

The peak was actually discovered by JO Nicholson while surveying the Himalayan range between 1845-50 and it was John Henessey who processed the data collected by former. However, Radhanath Sikdar made the crucial calculations which determined Mount Everest to be the highest in the world. This was not the only instance. Colonel HL Thuillier, the deputy director of GTSI along with Col F Smythe brought out The Manual of Surveying India and acknowledged in the Preface the contributions of Babu Radhanath Sikdar in writing several chapters and compiling several auxiliary tables. In the third edition following Radhanath’s death the acknowledgement was left out though the contents remained unchanged. No wonder, Brahmo leader, Shibnath Shastri who wrote about Radhanath Sikdar in Ramtanu Lahiri o Tatkaleen Banga Samaj did not mention his feat of calculating the height of the Mt Everest.

In another feat Radhanath, during additional charge of the Meteorological Observatory introduced the system of hourly observation which led to the first ever work on climatology of Calcutta, the first city where this was done. Ashish Lahiri in his monograph on Sikdar wrote, despite appreciation from superiors he had tried to leave Survey of India and Everest and Waugh had to resort to manipulation to retain him. A primary reason might have been the discrimination in pay between Europeans and Indians and moreover, his fearless nature led to clashes with high-handed White officials. One particular incident was cited by Shastri in which Radhnath paid a fine of Rs 200 but refused to apologise after intervening on behalf of his hapless coolies who were forced by the district magistrate to work for him. Following his retirement in 1862, he immersed himself in the task of simplifying the highly Sanskritised Bengali prose despite being well-versed in Sanskrit. He believed that written word should be comprehensible even to ordinary house wife. He founded and coedited along with another Derozian, Peary Chand Mitra – a Bengali monthly, Masik Patrika, sold for an anna a piece. He is said to have inspired Mitra to write Allaler Ghare Dulal in colloquial language. A scholar of Greek, Latin, English literature and philosophy he wrote many articles for the monthly. Shastri however observed, after being away from Bengal for years, his behaviour was more attuned to Europeans. His role in women’s education has remained largely unsung.

It is perhaps time to remember Radhanath Sikdar who scaled great many heights we hardly know about.