The Parsis of Calcutta A Waning Community

Sandip Banerjee

With the emergence of the City of Calcutta as the ‘Second City of the Empire’, this place started becoming more and more cosmopolitan. Calcutta, as a city is definitely much younger than many other cities in India. But it rose to unprecedented heights of prominence during the days of British Raj. As the root of British rule in India kept on becoming firm, Calcutta kept on improving as a city. The political and economic significance of the city went on multiplying, attracting people of various communities. They flocked in search of fortune. Eventually many of them settled in the city for a long time, leaving behind an indelible mark of legacy.

All these communities like the Parsis, the Armenians, the Jews have a story to tell in the built –up of the city of Calcutta. It might be that these people have become thin in number over the years; many of them migrated to other places and yet they cannot be withered away from the face of consideration. It is for them that Calcutta has remained such a colourful city. With passage of time Calcutta might have become Kolkata, even then the long drawn presence of some communities reflect an impression of the past glory of this great city.

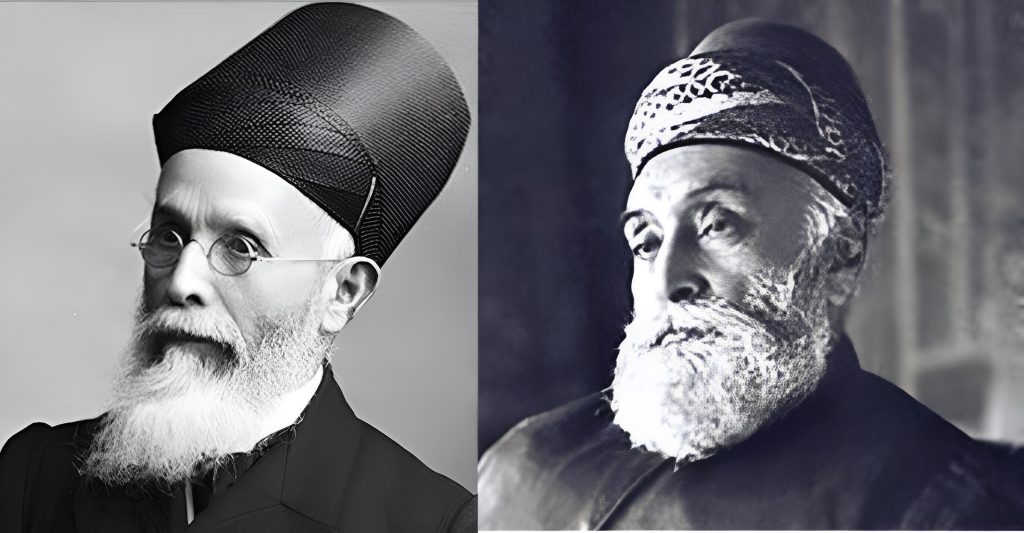

Calcutta once flourished as the capital of an empire, the bustling hub of commerce. The Parsis were the people who dwelt near the centre of commercial activities. They had undergone a somewhat strange alchemy; perhaps the arrival of the British acted as a catalyst, transforming an agrarian community to an entrepreneurial one. The earliest historical evidence of Parsi migration to Calcutta can be traced in 1767 in the form of a gentleman known as Dadabhoy Behramji Banaji who came from Surat. He was a flourishing trader, soon to receive the patronage of John Carter, then Governor of Bengal and who had known Banaji since his days in Surat. Behramji was the doyen of the famous Banaji family, later to make deep influence on the industrial history of Bengal. But the person who truly raised the name of the Banaji family was Rustomji Kawasji Banaji, who first came to Calcutta in 1812 and settled in the city. Rustomji Babu, as he was fondly called in the community founded the Sun Insurance Office and was also a known ship merchant. He was a personal friend to Dwarkanath Tagore. He not only owned a fleet of twenty seven ships; he actually bought the Kidderpore Docks in 1837. Rushtomji, along with his prowess in merchandising, also was a notable philanthropist. He founded the first fire temple at Ezra Street in 1839. The British honoured him among the twelve Justices of Peace created in 1835. He also played a key role in modernising the city of Calcutta. Regrettably he is forgotten today, just like most of the icons of his community who once haloed the city of Calcutta.

The journey of the Parsis to Calcutta is the account of some intrepid men who had left settled homes in the West to come to Calcutta to start a new life. According to the book ‘Pioneering Parsis of Calcutta’ written by Prochy N Mehta, the Parsis used to trade with Armenian traders in Surat. Later on some Armenians came to Murshidabad first and then to Calcutta. No wonder some Parsis took the Armenians to their heels and arrived at Calcutta. Unfortunately, though the Parsi community is almost 245 years old in Calcutta, yet there is very little historical documentation on them. The result is modern generation is almost ignorant about the achievements and contributions of the Parsi Community in Calcutta.

Among the first Parsi settlers in Calcutta (1780 onwards) was Jamshedjee Jeejeeboy who made his fortune in opium trade with China. There have been many illustrious families of the Parsis who flourished during the nineteenth and twentieth century rose from adversity to wealth and prominence by dint of their perseverance, hard labour and commitment. Seth Jamsedhji Framji Madan’s rise is one such glaring example of the Parsi spirit of sincerity and tenacity. Starting his career at the age of 12 as a screen shifter in a theatrical company at wages of Rs 4 per month, he eventually became ‘Madan Seth’ and started a prosperous company of his own. His deserves a special mention for his role in popularising and spreading Indian cinema industry. It was he who conceived the idea of public viewing of films. At the time of his death, he owned a considerable number of cinemas dotted all over the country. In recognition of his services and notable acts of charity, he was endowed with the honour of ‘Order of Britsh Empire in 1918’. It was he who created India’s first purpose-built cinema hall, the Elphinstone Picture Palace in Calcutta. Madan Theatres Ltd was the first exhibitor of the talkies in India. Some of the opera houses owned by Madan Theatres are The Electric Theatre (Regal Cinema), The Grand Opera House (Globe Cinema) and Crown Cinema (Uttara Cinema). It is only our misfortune that history has not done justice to the legacy of this great enterprising man, for how many of us know that the Madan Street located in the Dharmtolla area of Calcutta is named after Jamshedji Framji Madan.

Calcutta based Parsis have lived as a community whose representatives have engineered development and creativity. We can talk about M.N. Dastur and Co, a well-known firm for technical consultants; we can discuss names like C.R. Irani and his caveat with ‘The Statesman’. Bengalis and Calcuttans have been great appreciators of music. Some of the everlasting loving, lilting melodies of Calcutta, sung by the most popular singers have been orchestrated by a Parsi gentleman by the name of V. Balsara who had a rare talent of having command over virtually any instrument with his fusion of Western and Indian Classical Music.

The status of the Parsis in Calcutta started declining in pomp and splendour with the eclipse of the British Raj in India. The industrial accomplishments of the Parsis started waning after 1947. Huge commercial establishments started fading away and the gestures of generosity became confined to their community. The main problem has been in the steady decrease in the Parsis population in Calcutta. There was time, some hundred years back when the Parsi population was growing but since the 1960s and 1970s the wheel has started revolving in reverse. The young population of the Parsi community started moving out of the city for greener pastures like Canada, Australia and New Zealand and as well as to other Indian cities. The job scenario coupled with the poor industrial infrastructure in West Bengal over the last few decades primarily drove the city’s young Parsis out to other places.

Today there are about 500 Parsis remaining in the city but sadly not even 50 percent among them are young. While the Parsis community of Calcutta might not as prominent as the Parsi Community of Bombay, however, even then it would be not wise to consider the Parsi Community in present day Kolkata as to having completely degenerated as a community. Parsi food like ‘Sali Marghi’ or ‘Patra ni Macchi’ can still be found in Calcutta in places like 9, Bow Street, in Bowbazar area in ‘Manackjee Rustomjee Parsi Dharamshala for Parsi Travellers’. This 115-year-old Dharamshala is still operational. At present Parsis or those married to Parsis are allowed to stay here, although the dining is open to all.

There was a time some sixty years back when the Parsi community in Calcutta had around 2,500 members. Today, with only 500 members remaining, this community is slowly losing its significance in Calcutta. The Parsi Bagan Lane near Raja Bazaar Science College still stands with reminiscences of freedom struggle and Indian Psycho Analytical Society founded by Dr. Girindrasekhar Bose. Perhaps there is no Parsi living there at present. A historical survey about 250-year-old recorded Parsi existence in Calcutta and would certainly throw light on the various ways in which the Parsi community contributed to the development of the city, particularly in avenues of commerce and entrepreneurial initiatives as well as in acts of social welfare. It is pertinent that the meager number of Parsis living in and around Ezra Street should not desert this city for with them a race would obliterate from the face of Calcutta.